More Ideas for Supporting Pre-Intentional Communicators

This month, we’ve been talking about how to support individuals who are at the earliest levels of communication: the perlocutionary or pre-intentional stage. Although everyone goes through a stage at which behavior is considered communicative only because the partner perceives it that way, some individuals linger there for months or years.

What steps can SLPs take in order to help these children and adults have meaningful interactions and build more effective communication skills? Here are some prAACtical thoughts on the matter.

Prepare for Skepticism

Some people in the client’s life may not believe that there is real potential for communication growth. This is particularly true for learners who are a bit older. When children reach the late elementary school and are still at the pre-intentional stage, there is a tendency to fear that ‘real’ communication is beyond the learner’s grasp. In our view, that is rarely the case. VERY rarely. It is much more likely that the intensive supports that these learners need have not been provided. So, get ready to be met with skepticism when you go in to support these learners and meet it with cautious optimism. That’s not as hard as it seems because you know one thing that they don’t: This learner really CAN improve his/her communication skills.

Look to Significant Stakeholders to Help Set Priorities

One way to address their skepticism is to prioritize something important to the doubtful adults in the learner’s life. Find out what their biggest challenges and concerns are, and sift through those to find something that you can use to build a communication plan. In Julian’s case, the SLP and teacher agreed that their biggest concern was knowing what he liked and didn’t like. Because he seemed to accept everything with a low level of interest, they felt that he didn’t really have preferences and that stripped them of a critical intervention tool: reinforcement. That’s a valid point, of course, and we were willing to concede that. What we were NOT willing to concede was that this doomed the learner to a lifetime of being a pre-intentional communicator. Together, we could work to do some reinforcer preference testing, a systematic process for figuring out what people like (or, in some cases, what they dislike less than other things). In Julian’s case, we went with things that he didn’t knock off of his tray table right away (e.g., vibrating ball, juice box, music toy). We also looked beyond ‘things’ and found that he seemed to respond well to certain people1. Beyond that, we worked to build the array of things that he tolerated with the expectation that successful experiences with those things would help him grow to like them. For example, we paired something he seemed to like (music) with certain toys.

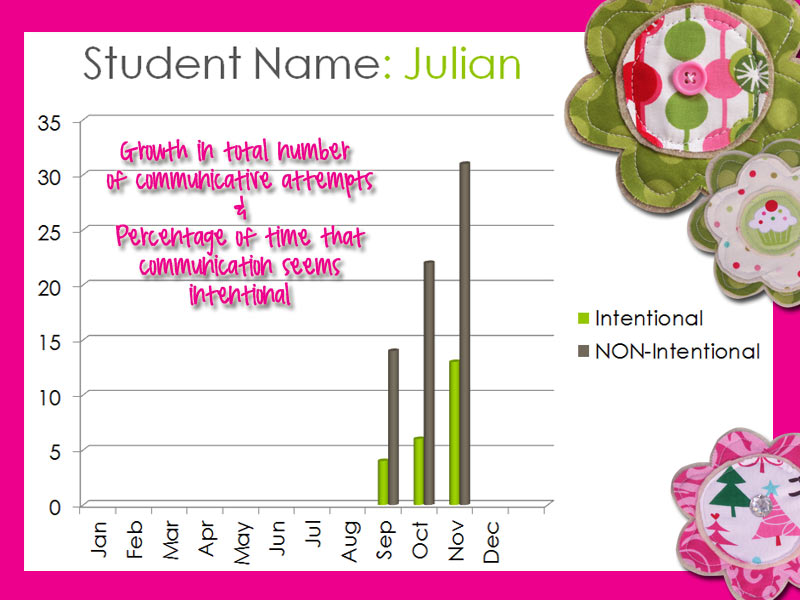

Once we had some ideas about what he liked, we could begin to present those in small doses. As they were presented, the team was able to observe his responses and record them. Responses were categorized as Seems Intentional or Does Not Seem Intentional. In Julian’s case, we saw a lot of growth in the total number of responses (from 18 to 44) and more modest gains in the percent of time that ‘The Signal’ was judged to be communicative (22% to 30%).

Build Interaction Routines

Another way to support communication learning is to create interaction routines. This involves a very simple structure with predictable elements, such as the verbal cue ‘Ready’ (pause), ‘Set,’ (pause), ‘Go’ (action)! Over time, we expect to see ‘The Signal’ or some other purposeful response during the pause time following ‘Ready’ and/or ‘Set’ in anticipation of the fun they will have after they hear ‘Go!’ Like other things, this works best when implemented consistently. Take the time to model this yourself when working with the learner, train team members, monitor, and reinforce their efforts. The hardest part is getting the team is in the habit of doing this. Once they do, learners tend to respond to the predictable structure and the positive consequences.

Build Understanding of Cause and Effect

Helping learners become purposeful in their communication is largely an experience of causality. They are learning that certain behaviors (e.g., The Signal) trigger positive outcomes. We can support them in making connections through other cause-effect activities, too. Experiment with the interactive use of switch toys, computer games, and cause-effect apps.

Use Touch Cues

Unlike the other strategies we’ve discussed, Touch Cues, are used to build receptive communication. They were originally designed for individuals with both hearing and vision loss, but can also be used with other learners who struggle to process oral language. The process is pretty straightforward: certain tactile cues (like a tap on the left shoulder) are used consistently to indicate to the learner that a certain thing will be happening. For example, Jillian’s team rubs her right forearm when they are going to take her out of her wheelchair. They tap the back of her elbow when they want to give her something to hold, and rub small circles between her shoulder blades they are moving her to a different location. Over time, the learner begins to make the connection with the Touch Cues we provide, and the resulting action. We accompany this with the same sort of verbal input as we would with any other beginning communicator.

Consistency Has Its Place

Consistency is important, but not in the same way for everyone. For interventionists, it’s critical. The more consistent we are in providing the intervention, the more quickly the learners will make the connections. In a perfect world, we’d be 100% consistent and learning would be optimized. In the real world, we aim for that and when we fall short, we get back on track as soon as we can. Life happens. The time spent beating ourselves up over what we didn’t do perfectly takes away from the time we have to move forward in the right direction. Better to just move on.

Consistency for the learner is another matter altogether. Simply put, as much as we may want it, we don’t actually expect it from learners at this level of communication. It is not usually something we set as a standard. Beginning communicators are often inconsistent. It is the norm, something to be expected. When typically developing children go through a period of developmental misarticulations, we notice it but don’t correct it. We expect that toddlers may produce /w/ for /r/ – it is part of the learning process. For pre-intentional communicators, expecting consistency is just not appropriate. Working toward it is fine, but we do so with the understanding that there are many valid reasons for inconsistency.

The Bottom Line

If you’ve made it this far, you already know the main idea: There are many things we can do to help pre-intentional communicators learn and develop their skills. Work on getting them to become more purposeful with whatever signals are most appropriate for your learners before expecting them to use picture symbols. This kind of intervention is fun, prAACtical, and rewarding.

If you’ve worked with communicators who are learning to be more purposeful in their expression, please share. We’d love to hear about your experiences.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

1Interestingly, the people to whom Julian responded were those who treated him like a communicator. They spoke to him, not at or about him, and engaged him in reciprocal interaction. Julian, in our opinion, chose wisely.

Filed under: Strategy of the Month

Tagged With: beginning communicator, cause-effect, consistency, preintentional communication, touch cue

This post was written by Carole Zangari

4 Comments

Carole, I thought this article was so apt for people with Rett Syndrome, I have modified it a little to reflect the difficulty girls and women with Rett syndrome have with apraxia, and posted it to the Facebook page about Rett Syndrome and Speech and Language Therapy that I run: https://www.facebook.com/groups/451858218222216/.

Thanks so much for the great ideas on this AAC site.

Thank YOU, Sally-Ann! I am off to search for it now. 🙂

This is another great resource and so encouraging! Thanks so much, Carole. You are doing such a wonderful service to this community!

Geri, what a nice thing to say! Glad this was helpful – so nice of you to take the time to comment. Really nice!! 🙂