How We Do It: AAC Strategies & Adaptations for Students in Support Walkers, Assessment & Funding

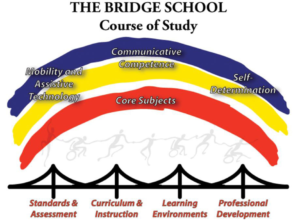

How can we reduce the negative impact of significant motor challenges on children who use AAC and are not independently mobile? Today, we conclude Christine Wright-Ott’s series on this topic. Christine is an Occupational Therapist and consultant at The Bridge School in Hillsborough California. She authored the chapter, Mobility, in several editions of the book, Occupational Therapy for Children. Christine lectures at universities and conferences including ATIA, Closing the Gap, ISAAC, ISS, and AAC by the Bay.

How can we reduce the negative impact of significant motor challenges on children who use AAC and are not independently mobile? Today, we conclude Christine Wright-Ott’s series on this topic. Christine is an Occupational Therapist and consultant at The Bridge School in Hillsborough California. She authored the chapter, Mobility, in several editions of the book, Occupational Therapy for Children. Christine lectures at universities and conferences including ATIA, Closing the Gap, ISAAC, ISS, and AAC by the Bay.

If you missed the earlier posts in this series you can catch up via the links below.

- Part 1: From Wheelchair to Walker: The Cascading Benefit of Hands-Free Mobility

- Part 2: From Wheelchair to Hands-free Walker for Preschool Children with AAC Needs

- Part 3: How We Do It: A Support Walker Mobility Program for Elementary Students with AAC Needs

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

AAC Strategies, Adaptations for Students in Support Walkers, Assessment & Funding

AAC Strategies and Adaptations

Post 2 and 3 described activities and opportunities preschool and elementary students at The Bridge School participate in, using hands-free support walkers, including recess, which is a burst of energy and controlled chaos for 15 minutes. Students have the option to choose activities they would like to do at recess using their Speech Generating Device (SGD) before being transferred into their support walkers. Experiences that are highly motivating at recess are videotaped for the students to review and are shared with familiar partners through conversations or writings using their AAC systems or social media.

A student uses her SGD to say she wants “to run in a race with her friend” at recess.

Running in her walker, she wins the race at recess!

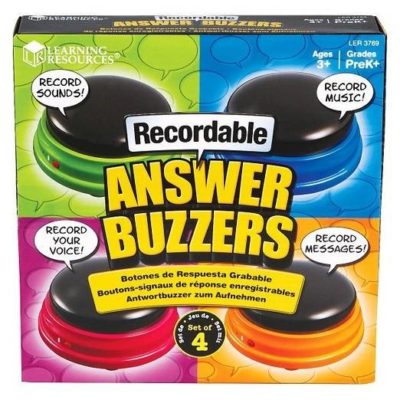

Students in support walkers rely on a variety of unaided communication strategies to interact with peers during recess (body language, listening, pointing, gestures, signing and using yes/no responses.) High tech Speech Generating Devices (SGD) are typically not attached to a support walker during recess, as they act as a physical and social barrier to accessing sports, playground games and peers. However, each student has a Step-by-Step or recordable answer buzzer, language boards or other low-tech devices attached to the frame of the walker with RAM mounts. The Step-by-Step and/or switch is usually placed behind the elbow for accessing prerecorded messages to peers.

A preschool student repairs his car. He uses a Step-by-Step with the yellow switch behind his elbow. A recorded message device is on the car.

A preschooler uses a switch at her left hand to access a Step-by-Step communicator. A Cheap Talk is mounted on the back of her walker with a RAM mount.

A preschool student raises her arms walking to the door in anticipation of pressing the button that says “open the door”. She has a Super Talker and Step-by-Step mounted with RAM mount on the back of her walker.

A preschooler uses a custom AAC device made with 4 switches connected to her Super Talker. It is mounted with a RAM mount and is swung away for outdoor play

Strategies and Adaptations

Most activities at recess do not need to be adapted for the students in support walkers. Students can participate with peers on the playground by running, playing hide and seek, kicking balls, playing soccer or tetherball and walking up the ramp and over the bridge on the accessible play structure. A peer buddy may be recruited to help a student in a walker to facilitate participation in a game. Students in support walkers can bring a novel activity to the playground to encourage interaction. Such activities have included a chalk drawing toy, miniature golf, a fashion show, Velcro ball and catch toys, bowling and a dance party.

A chalk drawing toy is attached to her KidWalk with a RAM mount.

The golf club is attached to her walker with Velcro

A basket attached to his walker with Velcro enables this student to carry and share toys with peers.

An elementary student in her walker meets her friends at recess, and they decide to put stickers on her shoes then walk around to share with peers.

A swim tube is cut and placed over this student’s arm with Velcro to act as a bat, so he can hit the ball off the tee.

Walker Assessment

The assessment should begin by defining the purpose for using a support walker, describing the environment(s) where it will be used (indoors, outdoors, uneven playground, fields) and identifying the features and options that best meet the physical and motor needs of the student. Most walkers are maneuverable indoors on smooth surfaces. If the child needs sensory input like jumping and spinning, then the KidWalk with its mid-wheel design, dynamic vertical and lateral movement for running and jumping is a good option. If the purpose for using a walker is to access recess and the student will be running outdoors over uneven surfaces, then a walker with a minimum of 8″ diameter wheels is suggested. Walkers that are designed with minimal hardware at the front of the frame are preferred so as to not interfere with reaching, leg movement while running and kicking and getting close to peers and objects (KidWalk, posterior Grillo and posterior facing Pacer.) The diameter of turning radius of a walker should be considered for ease of maneuverability, particularly indoors. A walker such as the Kidwalk with large mid-wheels or a walker with 4 swivel casters, like the Pacer (for indoors), will be easier to maneuver in tight spaces compared to a fixed rear wheel walker. A KidWalk with its mid-wheel design has a 40″ turning radius compared to a walker of the same size designed with a fixed rear wheel, which gives it a 70″ turning radius, requiring more space to move around. A mobility device should be evaluated in the child’s natural environment(s), particularly since most support walkers work efficiently on smooth hard surfaces, commonly found in a clinic, but not on other surfaces like carpets, playgrounds, sidewalks and fields.

In his wheelchair this student would get frustrated in circle time, kicking and banging his tray. A KidWalk was recommended and he spent most of the school day in it. He would leave circle time to spin and jump in his walker and return to the group more focused.

He created his own sign for his walker, labeling it his “jumper”. His motor control, strength, stamina and behavior improved.

Equipment and Funding

Manufacturer representatives and Rehab Technology Suppliers may loan equipment for use during an evaluation for a student. The Bridge School was successful in acquiring funding through grants to purchase support walkers for evaluation purposes. Authorization for a support walker may be pursued through the student’s school district when a mobility goal for inclusion in Physical Education or accessing activities at recess is included in the student’s Individual Education Plan (IEP). A family’s medical insurance might purchase a support walker for home use, which is transported to school by the family.

A low-cost option for recording a single message is this toy from Learning Resources which comes in a pack of 4, so each single message recordable button is about $4.00 USD.

A switch is attached to this adjustable RAM mount which is clamped to the walker. www.rammounts.com

Resources and Links

- The Bridge School website offers a free course of study with articles and photos of students participating in classroom activities. This is the direct link to articles on standing mobility with support walkers at Bridge School including photos.

- I Can Walk 2: A website describing the benefits of self-initiated mobility which includes information on the KidWalk Support Walker along with information on mobility and videos of users. http://www.icanwalk2.com/benefits.html

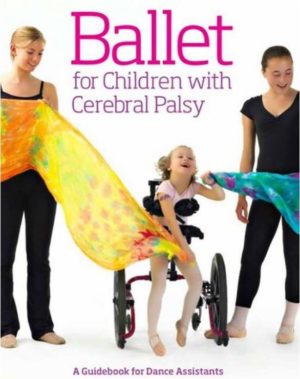

- This ballet guide book can be downloaded for free. It provides information on cerebral palsy, how to encourage more motor learning with children, how to encourage body awareness and participation, and ideas for an adapted ballet program.

Manufacturers of Walkers

- http://primeengineering.com/ KidWalk, ProneWalk

- https://www.rifton.com/ Pacer

- https://www.mobility-usa.com/grillo–gait-trainer.html Grillo

- http://www.r82.com/products/walking/mustang/c-23/c-72/p-220/?sku=53732 Mustang

References for this Series

Adolph, KE., (2014). The costs and benefits of development: the transition from crawling to walking. TOC. Vol 8, (4) Dec., 187-192. DOE: 10.1111/cdep.12085.

American Academy of Pediatrics (2013). The crucial role of recess in school. Pediatrics, 131,1. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2993

Anderson, D. Campos, J. Witherington, D. Dahl, A. Rivera, M. He, M. Uchiyama, I. and Barbu-Roth, M. (2013). The role of locomotion in psychological development. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 440.

Campos, Joseph & I. Anderson, David & Telzrow, Robert. (2009). Locomotor experience influences the spatial cognitive development of infants with Spina Bifida. Zeitschrift Fur Entwicklungspsychologie Und Padagogische Psychologie. 41. 181-188. 10.1026/0049-8637.41.4.181.

Graham D., Lucas-Thompson R., O’Donnel M., (2014). Frontiers in Public Health. May 28, 2:58. 1-18.

Haapala H., Hirvensalo M., Laine K. Laaks L. Hakonen H. Kankaanpaa A. Lintunen T. and Tammelin T. (2014). Recess physical activity and school-related social factors in Finnish primary and lower secondary schools: cross-sectional associations. BMC Public Health. Published online 2014 Oct 28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1114.

Kretch, S., Franchak, J., Adolph, K., (2013). Crawling and walking infants see the world differently. Child Development, 4, 1503-1518. DOI: 10.1111/cdev.12206.

Murray, (2016) www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2012-2993

Nilsson, L., Communication mediated by a power wheelchair. Disability Studies Quarterly, Vol 31, No 4 (2011).

Oudgenoeg, P. Volman, M. Leseman, P. (2012). Attainment of sitting and walking predicts development of productive vocabulary between ages 16 and 28 months. Infant Behavior & Development, 35(4):733-6. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.07.010.

Rendeli, C., Salvaggio, E., Sciascia Cannizzaro, G., Bianchi, E., Calderelli, M. & Guzzetta.E (2002). Does locomotion improve the cognitive profile of children with meningomyelocele? Child’s Nervous System, 18, 231-234.

Rivera M. (2012). Spatial Cognition in Infants with Myelomeningocele: Transition from Immobility to Mobility. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, San Francisco, CA: ProQuest, UMI Dissertations and Theses. Publication Number: 3553864. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5623c0k6

Therrien M., Light J., & Pope L. (2016). Systematic review of the effects of interventions to promote peer interactions for children who use aided AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 32, 2, 81-93.

Tomporowski PD. (2016). Exercise and Cognition. Pediatric Exercise Science. 28, 1, 23-7.

Walle, E., Campos, J., (2014). Infant language development is related to the acquisition of walking. Developmental Psychology, 50,2 , 336-48. doi: 10.1037/a0033238.

Wright-Ott, C. Mobility. In Occupational Therapy for Children, Seventh edition, Case-Smith, 2015. Elsevier Mosby.

Filed under: Featured Posts, PrAACtical Thinking

Tagged With: mobility, mounting, schools

This post was written by Carole Zangari

1 Comment

I am so glad to have found your website! My son is 2 years old and has a lengthy list of rare medical conditions that leave him globally delayed and also deaf. We will be getting his very first AAC Device next month and I could not be more excited! We have been working with him on ASL for over 1.5 years and he is very slowly picking it up but doesn’t understand more than a few words and only mimics “more” occasionally. I look forward to reading all of you posts about strategies to help him. I thought I should ask though, if there are any additional information that you could help with? We are very new to all of this so any help is appreciated! I blog at https:AmyScrapSpot.blogspot.com if you would like to check it out!