How I Do It: Addressing the 4 Most Overlooked Operational Skills for High-Tech AAC Users

Like many of you, the best part of the work week is when I get to teach language. As amazing as it is to help people with AAC needs become more linguistically competent, we have to be sure not to shortchange some of the operational skills that allow AAC learners to be successful. In this post, SLP Rachel Madel helps us think about supporting the development of operational competence in our AAC learners.

teach language. As amazing as it is to help people with AAC needs become more linguistically competent, we have to be sure not to shortchange some of the operational skills that allow AAC learners to be successful. In this post, SLP Rachel Madel helps us think about supporting the development of operational competence in our AAC learners.

The 4 Most Overlooked Operational Skills for High-Tech AAC Users

The 4 Most Overlooked Operational Skills for High-Tech AAC Users

When I first began helping children use high-tech AAC systems, I focused all of my energy on building strong communicators who could navigate through complex systems and use powerful language. I quickly realized that if I wanted to optimize the use of AAC I also needed to teach my students the mechanics of the machines they were using. Once I began teaching basic operational skills, I noticed a remarkable difference in my client’s ability to communicate more independently. Cultivating operational competence is crucial for fostering independence and self-advocacy skills.

Below are the top 4 operational skills that I try to weave into my sessions with children using high-tech AAC.

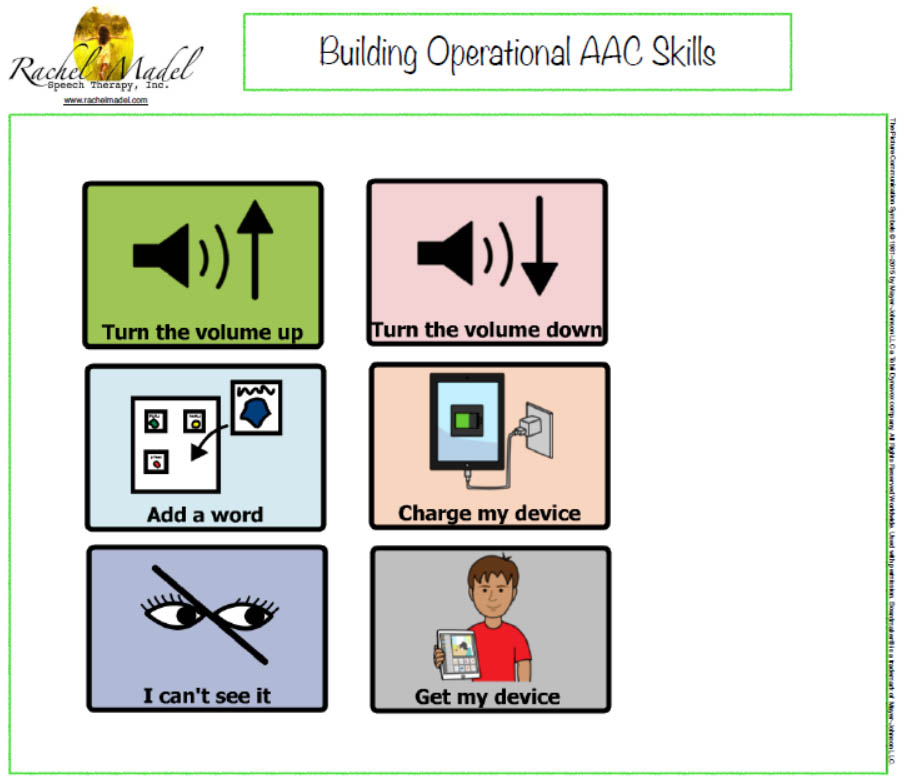

1.) Volume

Just as we would help a soft-spoken child learn how to raise their speaking volume, we must also teach high-tech AAC users how to regulate the volume on their device. For example, I have a student who came to see me after his weekly visit to the library. His aid would often turn the volume down to a whisper during library time. Instead of immediately turning up the volume for him, I used these moments as a teaching opportunity to impress upon him the importance of recognizing when operational issues create a communication breakdown

I modeled a typical response (e.g.,“What?” and “I didn’t hear you”) and then demonstrated adjusting the volume to an appropriate level. We experimented with various volumes, in a variety of settings, so that eventually checking his volume level became routine. Initially, I would wrinkle my face with an exaggerated “Huh?” or demonstrate gestural communication by holding my hand up to my ear. When it was too loud, I quickly covered my hands over my ears to cue him to turn it down (which he thought was quite amusing).

With practice like this in the beginning of our session, he began understanding the communication breakdown that occurred when his volume was too low and he began adjusting the volume on his own. I’ve found this type of practice works best with kids who are a little bit older (think 3rd grade and up) and who are receptive to reading facial expressions. With my younger kids or children with access issues, I adjust the volume for them. However, I always make sure to pair with “up” and “down” so that they are still and active part of the process.

2.) Visual Access

Just as we need to be mindful of the volume of these devices, we also have to make sure that children are able to access their devices visually. Therapists often focus significant energy on visual access in the beginning stages of AAC by determining if a child needs a mount for their wheelchair or high/low contrast for their visual display. However, we must also make sure children are able to advocate for more minor adjustments according to lighting in the room or positioning of their device.

About a year ago, I worked with a 6-year-old boy with autism who kept picking up his device and bringing it close to his face. Initially, I chalked this up to a stimming behavior but then realized he wasn’t able to properly see the screen. The iPad is notorious for automatically lowering screen brightness to conserve battery life. Once I showed him how to adjust the brightness, he became fixated on sliding the brightness up and down (this WAS a stimming behavior) but eventually we settled on a brightness that allowed him to easily see the screen.

I typically target screen brightness during highly motivating iPad games or videos since there is a high level of engagement. If a child can’t see their favorite video, there is genuine motivation to do something about it. Similarly, I help children position their device by showing them how to prop open a stand or clear off space on the table to make room for their device. I model first, and then help the child do it on their own. For children with limited mobility or younger children, I focus on the phrase, “I can’t see it,” by showing them a visual cue card or creating a button on their device.

3.) Adding Vocabulary

I’m currently working with a 9-year-old boy with autism and, without fail, each week he is fixated on something new. One week it was pipe cleaners, the next it was balloons. This week, he loves stoplights. He will often attempt to request these items and, after several unsuccessful attempts, he will then type the word into his device.

Very diligently, he types his new favorite word repeatedly because he’s excited to talk about them.To help him quickly access these words, I created a folder with his “Favorite Things” and then every session we practiced adding new words. I took him step-by-step through the process of adding a new button and eventually he began adding new words on his own.

This type of activity only works for children who demonstrate both strong typing and device navigation skills. When I’m working with younger children, I focus on moments when they are searching for a word but don’t have it. I use a visual cue card saying, “Add a Word,” to help children begin requesting the addition of new words to their device. Children get excited about having new words at their disposal so I make a point to model new vocabulary in as many ways as possible.

4.) Charging

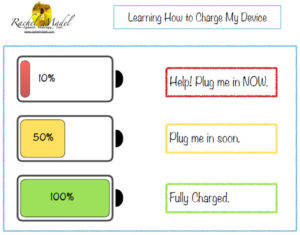

Nothing is quite as frustrating to a child as attempting to say something only to find their speech-generating device inoperable because the battery has died. When this happens, the path of least resistance is to quickly find an outlet for the child, but in doing so we may miss a valuable teaching opportunity.

The first step is to help the child understand when the battery is dead or about to die. I use a visual cue card to help students understand their device’s battery life is diminishing and they need to find an outlet. With my older kids, we work on getting the charger out of their backpack, finding a suitable outlet and plugging in the device (Portable chargers have become a game-changer). When possible, I set up a designated “charging spot” where the charger is already plugged in and ready to be connected. Like anything else, when the process is simplified, children become more willing to participate.

You can also help families create charging routines where they help their child plug in the device at bedtime to ensure they are fully charged the next day. For early learners, I use a visual cue card that says, “Charge my device” and then set it up so that they simply plug it in.

Keep in mind that it takes time for children to learn and use these operational skills independently. Many of the children I work with benefit significantly from my visual cues (which you can download here) and continue to make steady progress. My hope is that with lots of repetition and experience, my children will enhance their understanding of the technical aspects of their device, leading to more independent communication.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Rachel Madel is a Los Angeles based speech language pathologist who is on a mission to help empower parents and educators by demystifying the use of AAC for children with autism. You can follow her on Facebook or Instagram for instant access to valuable AAC resources. Know parents struggling with Communication? You can also sign up here to download Rachel’s Core Word Communication Board + Starter Guide for parents.

Filed under: PrAACtical Thinking

Tagged With: high tech, operational competence

This post was written by Carole Zangari

4 Comments

Hi all very important skills that combined together will produce a competent high tech aac user. All of these skills my daughter has managed but I find the Teaching Assistants helping her need to understand these few steps too. I went into school for a meeting & my daughter had been placed with her back against a full floor to ceiling wall of windows on a very sunny day. It didn’t occur to them to just drop down to her eye level & see just what the screen looks like. Also had to point out plugging in to charge leaving the cable stretched across a room full of students in a science lab was not the best idea.

Hi Trudi, It’s sometimes the simplest things that we forget to think about! Like getting down on the child’s level. It’s sometimes a challenge to get support personnel on board with AAC. Best of luck in your AAC journey 🙂

Well Rachel, beyond all the talk of core vocabulary & communication intention, this is one of the most empowering suggestions that I’ve seen in years! Thank you so much for reminding us that there is so much more to being a powerful system user than what a person says. These operational controls/competencies, often so overlooked by many therapists, teachers & parents, can be the “tickets” to personal ownership & embedding the idea that this is MY voice, MY tool to MY world into how people know and respond to ME, not because someone told me to do it, but because I told them! Many Thanks!

Kelly, Thank you so much for such kind words! I couldn’t agree more… empowering children instead of merely instructing them. Thanks again!