Visual Supports in AAC Therapy with Older Students and Adults

When learners are still struggling with communication in their teenage years and beyond, it means we have a lot of catching up to do. There are lots of implications for us as SLPs, of course, but the main one is this: Every interaction should have a purpose. As we head to the waiting room or classroom to see this student, we’re focused on how we can elicit practice on meaningful skills in the next few minutes. On a good day, we can use these few minutes before the session productively. Before we get to the therapy room we try to:

- use expectant pauses and graduated prompting to elicit a greeting at his/her highest level

- engage him/her in conversation to practice social exchanges

- provide opportunities for him/her to respond to a non-obligatory communicative context and facilitate a response

- make basic requests, like asking for help to open the door that we’ve conveniently blocked with a foot

- practice social etiquette, like ‘thank you’ when someone steps out of the way or ‘excuse me’ if we bump someone

- help them use a vocabulary word that was taught recently

- gain experience in initiating conversation with less familiar partners, such as greeting the front desk staff or people we see in the hallway

- work on generalizing a skill he/she uses with us to other communication partners, such as the receptionist, classmates, or other people in the waiting room

It doesn’t always work out that way, but we strive to make every moment count. With older learners, we feel the intense pressure to make meaningful communication gains.

This month, we will be revisiting some of the therapy strategies and ideas we’ve written about before and reframing them to address the needs of adolescents and adults who use AAC. In this post, we’ll look at ways in which we can use visual supports to continue to support language learning and emotional regulation.

Emotional Regulation and Social Understanding

Visual supports for emotional regulation aren’t just for beginning communicators, people with intellectual disability, or those on the autism spectrum. In fact, they can be very helpful for a broad range of experiences. I was reminded of this recently when a friend had to go for a very painful medical procedure. To cope with her anxiety, she took along a photo of her little dog so that she could glance at it in the waiting room and during the procedure. Guess what? It worked! There is nothing wrong with the intellect or sensory processing of this fine woman, but using a visual support was highly effective for her nonetheless.

One way to use visual supports to help AAC learners is to work with them to write down a list of steps, considerations, or guidelines that they can use in difficult situations. Here are some we’ve used for:

- Handling disappointment

- Saying the same thing repeatedly

- Dealing with unfair situations

- Being ignored

- Personal responsibility

- Seeing other points of view

If you want to take a closer look, you can download this packet here.

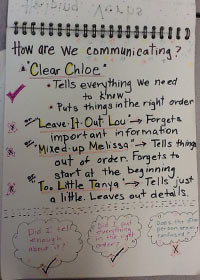

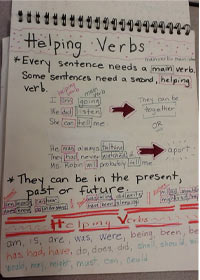

Remembering Key Ideas

Another kind of visual support that we use with adolescents and older clients resemble the anchor charts you sometimes see in classrooms. The idea is to have a clear, concise summary of a key idea. We’ve used them for grammar, pragmatics, and syntax. Here are some examples.

They are easy to make with materials you already have on hand (paper, markers), but we’ve found that it takes a little thought and planning to capture the right idea with the right verbiage. We generally sketch out a draft on scrap paper first so we can play around with the layout and wording. Even with that step, it generally takes about 15-30 minutes to make a tool that is used repeatedly in our sessions. You can take a picture of it and print that or email it to your client if that seems appropriate.

Are you using visual supports with teens and adults? We’d love to hear about those experiences.

Filed under: Strategy of the Month

Tagged With: adolescent, adult, anchor chart, download, resources, teen, visual supports

This post was written by Carole Zangari