The PrAACtical Power of the Perception Wheel

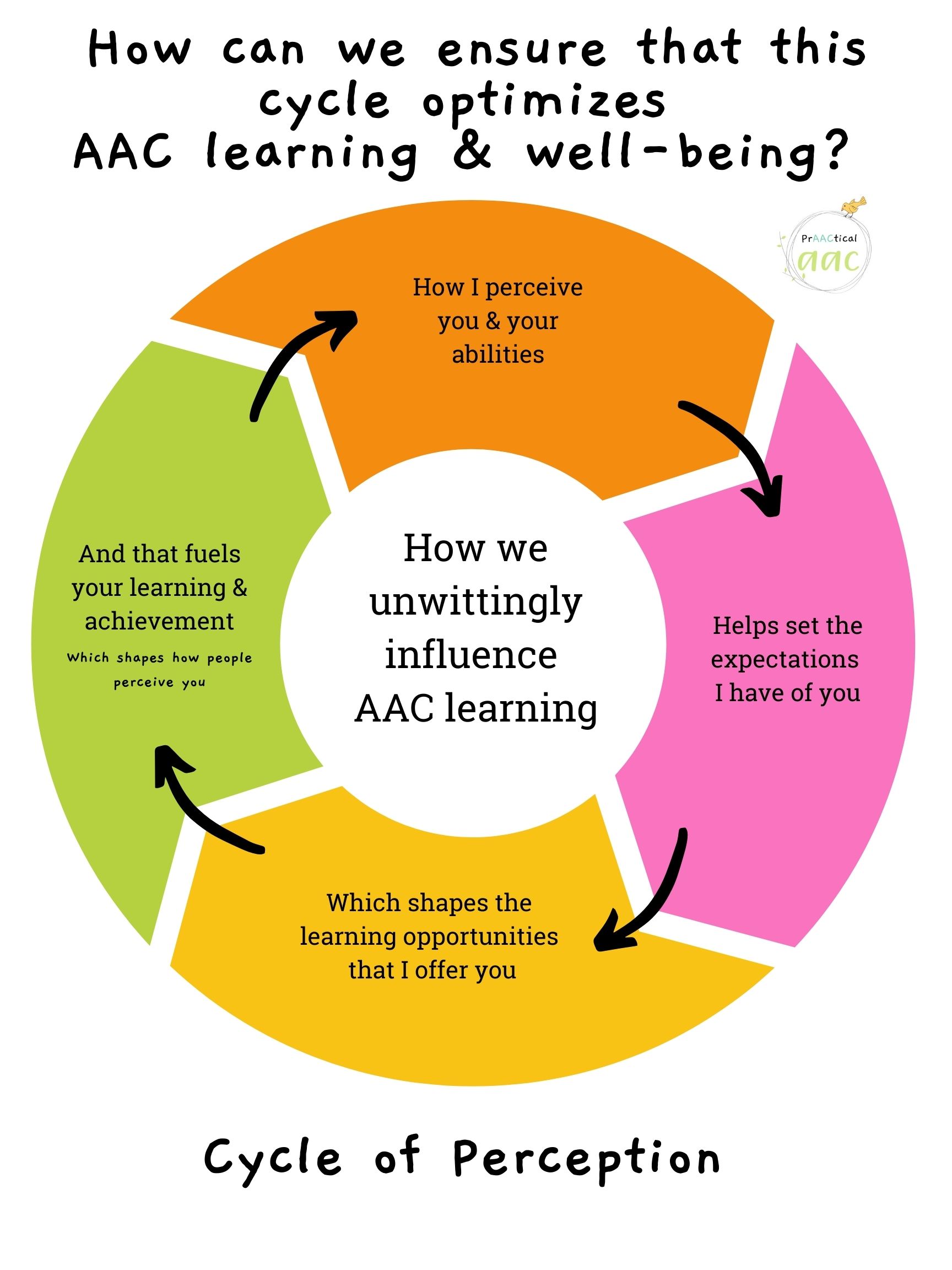

In a previous post, we talked about a cycle that influences AAC learning. Depending on how things start, the cycle can develop into a downward spiral or set a more positive trend line into motion. This is something worth thinking more about.

When I was a college student, I worked with a small group of men with intellectual disabilities who were leaving the residential institutions where they had lived since childhood in order to live in the community. It was a lot of responsibility for a 19-year-old but turned out to be one of the most influential experiences of my early career as an SLP.

I learned a lot from Bob, who was in his early fifties and one of the most congenial people I’ve ever met. Though limited in many ways, he was truly gifted in his ability to connect with people. Bob’s twinkling eyes and strong people skills turned strangers into acquaintances and acquaintances into friends. I was fascinated.

One of the things that set Bob apart was his mastery of the niceties of interaction. Whether you were the teller at the bank where he opened his first account, the grocery store clerk, his landlord, or his doctor, Bob beamed when he spoke to you. He used his small vocabulary, limited grammar, and dysarthric speech to make you feel special.

He shared an apartment with Bill and Joe, neither of whom were initially successful in connecting with the people in their new community. Bill was a good incidental learner, though, and became Bob’s shy sidekick within a few weeks. Joe was more reticent and often had a dark mood. On a good day, he could be abrasive, and there weren’t that many good days in the beginning.

But off we went to explore the neighborhood. We opened accounts at the bank and bodega. We got haircuts. We shopped for food, ate out when the budget would allow, and went for ice cream on summer nights. We took the incline down Mount Washington and rode the bus most of the time.

In Bob’s eyes, every interaction was a chance to make a new friend. Beyond a friendly greeting, he wasn’t quite sure what to say or do, but he was consistent with one thing. He always, always, always said ‘please,’ ‘thank you,’ and ‘excuse me’ when the situation called for it.

And when he did, the response was equally consistent. People smiled. They talked to him like a real person (not such a common thing in the late 1970s when people encountered adults with significant disabilities).

And when we returned the next time, they remembered him. They smiled. They engaged with him. Some of them even initiated interactions with Bob.

Not Joe. Not Bill. Just Bob.

After a few months, something happened that helped people warm up to Bill also. He started saying ‘please,’ ‘thank you,’ and ‘excuse me’ just like his buddy, Bob. The change in the store clerks, bus drivers, and servers was immediate. They looked him in the eye rather than just engaging with Bob. They smiled at him. They began treating him as a more competent individual. They complimented him, asked questions, and waited for answers. And Bill began to thrive.

Is there really so much power in ‘please,’ ‘thank you,’ and ‘excuse me’? Probably not, but it fueled my emerging sense of clinical curiosity. It certainly seemed like there was a tiny bit of magic in those words. It seemed like they changed how the community members saw Bill. They perceived him differently than they had the week before. They saw him as someone worth talking to.

They saw him as someone who belonged. And that changed everything.

They perceived Bill in new ways that led them to expect more of him. And because they had higher expectations they interacted with him differently. They shifted to conversational changes that gave him more dignity and agency. They spoke to him more like any other customer, expecting and waiting for a response. Even when that response was nonverbal or a simple acknowledgment, it worked. They continued the interaction briefly until the bank deposit, the shop purchase or meal order transaction was complete. They treated him just like anyone else, but with a little extra patience and encouragement.

The new approach they were taking was not lost on Bill. He was less hesitant and smiled more. He engaged for longer utterances and took more turns. He used language when he could. He became more confident and outgoing. He shined in ways that he hadn’t before.

When we went to new places, Bill largely retained the new conversation skills and habits he had developed with familiar clerks and shopkeepers. He used them at the library, at new shops, and at restaurants we hadn’t visited before. For the most part, those new communication partners seemed to treat him with higher levels of respect and expectation than what we had experienced just a few months ago. They perceived him as capable of holding conversations typical of those venues.

An upward spiral was in motion. The wheels were turning in exactly the way that Bill needed them to.

Perceiving him as capable led to expectations for more normalized interactions. And those interactions often stretched Bill past the upper limits of his skill set. Over time, Bill’s upper limits got higher. And the more sophisticated his conversation skills became, the more they judged him as a competent customer. In terms of Bill’s growth and acceptance in the community, things were spiraling upward.

Our perceptions can launch a cycle that goes either way. Can we facilitate the upward trajectory of the spiral so that the cycle leads to more positive things in the lives of AAC users? Bill would have said, “Sure ‘nuf.”

Let’s make it happen.

Filed under: Featured Posts, PrAACtical Thinking

This post was written by Carole Zangari

1 Comment

Love this, thanks for sharing. It seems small but is actually a skill that makes a huge difference.