PrAACtical Research: Recasts in AAC Mediated Interaction

Today, we welcome back guest author Dr. Kathy Howery for another wonderful discussion of an important AAC research article. Dr. Howery’s work in AT and special education spans three decades and her research uses phenomenological methods to increase our understanding of the lived experience of people who use AAC. She works with the Ministry of Education low incidence team, and as a consultant to schools and school districts across Alberta focusing primarily on children and youth with complex communication needs. In this post, Dr. Howery reviews an important article describing research on recasting in AAC mediated conversations.

Today, we welcome back guest author Dr. Kathy Howery for another wonderful discussion of an important AAC research article. Dr. Howery’s work in AT and special education spans three decades and her research uses phenomenological methods to increase our understanding of the lived experience of people who use AAC. She works with the Ministry of Education low incidence team, and as a consultant to schools and school districts across Alberta focusing primarily on children and youth with complex communication needs. In this post, Dr. Howery reviews an important article describing research on recasting in AAC mediated conversations.

Recasts in AAC Mediated Interaction

Soto, G., Clarke, M. T., Nelson, K., Starowicz, R., & Savaldi-Harussi, G. (2020). Recast type, repair, and acquisition in AAC mediated interaction. Journal of Child Language, 47, 250-264. https://doi.org/10.1017/S03035000919000436

What this article is about (the focus of the research)?

This article focuses its attention on the power of recasts and repair scaffolding language development in children with severe motor speech disabilities who use speech-generating technologies to communicate.

Recasting is an adult reformulation of an immediately preceding child utterance where the adult provides a more complex or more accurate linguistically structured model of the utterance while using some elements of the child’s utterance and maintaining the child’s intended meaning.

Repair can best be described as a child immediately changing their initial utterance to take on some aspect of the recasting provided by the adult. An example would be a child says “daddy shoe” pointing to her daddy’s shoes near the front door, to which an adult responds (recasts) “Yes those are daddy’s shoes” and the child says “daddy’s shoe” or “daddy shoes” or perhaps even “daddy’s shoes” repairing some or all of the linguistically incorrect elements of their original statement.

The authors note that “adult scaffolding of child language through the use of recasts is one of the most commonly adopted intervention approaches in programs designed to facilitate grammatical development in children with language difficulties “(p. 251). They point to research that supports the use of recasts as interventions with children with autism spectrum disorder, specific language impairment, language learning disabilities, and for children and youth with motor speech disorders who use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC.

An overview of the evidence supporting the benefit of immediate repair on language acquisition pointing in particular to the research with second language learners, children with little or no functional speech who rely on speech-generating technologies (Clarke et al. 2017), and in young children learning aided AAC (Romski et al., 2010). The authors suggest that repair not only supports language development, but it also helps the child learn about their device’s language storage infrastructure, and supports the establishment of motor planning.

While they note that evidence indicates positive relationship between adult recasting and acquisition of novel vocabulary in users of AAC, there is no evidence that explores the relationship between the type of recast provided by the adult, the rate of repair done by the child, and the spontaneous use (therefore acquisition) of the linguistic target.

That is then what this study sets out to explore- the relationship between the type of recast, child repair, and child spontaneous use of linguistic targets in children with severe motor speech disabilities who use speech-generating generating devices.

How they gathered their information:

The information for this study was obtained from data gathered during a previous study of the effects of a conversation-based intervention on children’s production of pronouns (e.g. I, he, she, you), verbs (e.g. go, like, put, get), bound morphemes (e.g. pre-, dis-, un-), and spontaneous clauses ( i.e. an idea or a statement that can stand alone) (See Soto & Clarke, 2017).

Participants in the original study, and therefore also in this study, included eight children (3 girls and 5 boys) between the ages of eight and thirteen years who had speech and motor disorders impacting their ability to use function speech. All participants used an SGD. Inclusion criteria for participation included: the ability to display operational competence at Level III on the AAC Profile (Kovach, 2009); the ability to formulate messages through direct selection or step-scanning; having English as their primary language; using mostly single-word utterances in daily language interaction; functional vision and hearing; and having significantly unintelligible speech.

The data for this study was drawn from 60 transcripts, which represented 43.88 hours of clinical interaction. The transcripts included utterances generated by the child and the adult during the intervention sessions. It should be noted that any use by the child of a pre-stored utterance was excluded from the analysis. In order to explore change in language use over time, the authors randomly selected transcripts from the first six (which they identify as “earlier”) intervention sessions and then from the last six (which they identify as “later”) intervention sessions for each of eight participants.

In order to answer the research questions, the authors first identified every turn sequence where adults recast child utterance. They then classified recasts into two groups: recast alone or recasts where there was also a prompt for the child to repair their message using means such as direct verbal encouragement or gesture (e.g., pointing to the linguistic target on the device) (p.256). Recasts without prompts were further classified into declarative recasts (reformulation of a statement), non-inverted interrogative recasts (A: What do you want? C: playground A: You want to go to the playground?) or an interrogative choice where the target is presented as a choice (C: I want for Christmas from Santa Claus. Dora backpack A: I want a Dora backpack for Christmas or I was a Dora backpack from Santa Claus?). And finally, they examined if the child’s utterance (turn after recast) to determine whether the child repaired their original utterance by incorporating parts of the adult’s recast/model (partial repair) or all of the adult’s modeled words (full repair).

To answer the question what is the relationship between child repair and spontaneous use of linguistic targets, Soto et al. sampled from all of the words model as recasts across participants and sessions. They then looked at the 15 words most frequently used by typically developing school-aged children of comparable developmental age in the United States. Those 15 words had been targeted during intervention across all participants. These words were: I, it, he, she (pronouns) am, is, was, were (copula forms), go, went, like, like (verbs), the (article), because (conjunction), and to (preposition). Calculations were then done to see which of those 15 words had been:

- a) recasted or recasted plus prompted;

- b) repaired by the child immediately following adult recast or plus prompt to repair; and

- c) used spontaneously (not following a recast or prompt) by the child.

Finally, they also identified words that the children had used spontaneously in later sessions that had NOT been used spontaneously in earlier sessions to see if they had been found in a recast –repair sequence in the earlier sessions.

What the authors learned from their study:

In order to share what the authors found I will, as they do, break the results down into answers to their two research questions.

Question 1. What is the relationship between the type of recast and child repair?

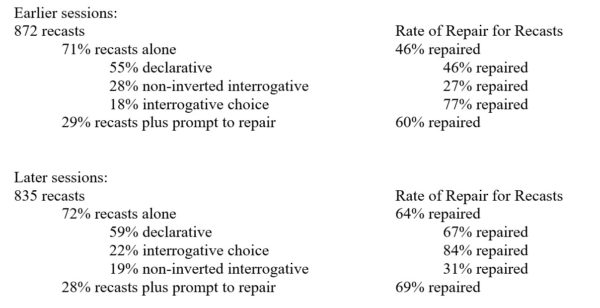

In an effort to present the data in a more easily understandable I have chosen to put it into a series of three tables.

Overall results:

- Rate of child repair for recasts presented alone – 52%

- interrogative choice – 81% rate of repair

- declarative recast – 57%

- non-inverted interrogative recast – 29%

- Rate of repair for recasts of any time followed by a prompt was 64%

Statistical analysis on the data indicated that recasts followed by a prompt to repair yielded a significantly (p<.001) higher rate of child repair than recasts presented alone. Additionally, the authors found a significant relationship between the type of recast and rate of child repair (this can be seen in the tables above with interrogative choice recasts clearly yielding the most repairs by the children).

So one can say, recasting helps to encourage the child to repair their utterance, recasting with a prompt for repair helps more.

And, the kind of recast matters! Or, all recasts are not created equal.

Question 2: What is the relationship between child repair and spontaneous use of linguistic targets?

No child showed spontaneous use of the 15 words targeted in the study during the baseline session (prior to intervention).

Only two children showed spontaneous use some (Child 1 I, Child 2 He She am is the and to) use of the linguistic targets in the early intervention sessions.

All eight participants showed spontaneous use of at least one target in the later intervention sessions.

Following the statistical analysis based on the six participants who spontaneously used four or more targets during the later session, the authors suggest that the repair of the linguistic target during earlier sessions may have contributed to its spontaneous use in later sessions.

Their conclusions therefore were:

- When recasts are followed by a prompt to repair, children are most likely to do so.

- There is a significant relationship between the type of recast and the child repair. It appears that this is based upon the participants’ “in the moment” evaluation of the pragmatic functions of the recasts. Interrogative choice was commonly treated as forced-choice where the child was obliged to choose one of the options presented by the adult. Non-inverted interrogative choice, in contrast, could be responded to with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Further, their findings were consistent with existing research in AAC that suggests a relationship between child output and learning of linguistic targets. While adult input is crucial, this study reinforces the idea that “input alone is not sufficient to cause change in a child’s communicative competence when using speech generating technologies’”(p. 261, emphasis added).

They conclude by suggesting for children who use SGDs language use through immediate repair may be critical for long-term word retrieval and use; perhaps due to the extra demands of the device (organizational structure of language, motor plans, etc.) far more so than is the case for naturally speaking children.

Why is this article important for practice?

There are several reasons that I believe this article is important for AAC practice.

- Firstly, although perhaps one shouldn’t have to point this out, this article implicitly stresses the importance of therapeutic language intervention for children and youth who require AAC. This may be something that most clinicians, at least in the United States, take for granted, but in my experience in my province in Canada, it is not. In my experience children and youth with complex communication needs who are learning to use SGDs to communicate more effectively with others and to develop language are often followed by a consultative model with little to no direct therapy being provided by speech-language pathologists. The Soto et al. article, along with others they cite such as Binger, Maguire-Marshall, & Kent-Walsh (2011) and Romski, et al. (2010) point to the fact that like other children who experience challenges in learning to express themselves effectively through language, children and youth with AAC need and deserve the kind of systematic, evidence-based therapies that we seem to take for granted for children and youth with fluency dysfunction, specific language impairment, dyspraxia, and so on. The evidence that systematic language intervention makes a difference is clear from this work. It is I would argue the role of all of us who are involved in supporting children and youth with complex communication needs to be effective communicators through language, albeit not alternative forms of language, to advocate for what this and other research suggests is necessary.

von Tetzchner (2017) suggests AAC is a “AAC represents a developmental pathway to communication and language competence”, it behooves us to treat it as such.

- So given my previous argument that this article reminds us that children and youth who are learning to use SGDs need language therapy, the second reason this article is important is that it provides clinicians with guidance to maximize the effect of their interventions by including a range of recasts and prompts for the child to repair.

Soto et al.’s research suggests it is not merely recasting that is important but that we must provide a variety of recasts and prompts. If, for example, our recasts were primarily non-inverted interrogatives e.g. C: puppy A: Do you see a puppy? it was shown to be far less likely for the child to respond with a repair perhaps even when prompted as they can just say “yes”.

Therapy sessions, as well as suggestions for teachers, parents, and others interacting with children and youth who are learning so speak through SGDs need to be informed by the idea that not all recasts are created equally, and we can use this along with other research in the field of AAC to thoughtful interact and support interactions that grow language, both receptively AND expressively.

- Which brings me to the third reason that this article is important for practice. That is, that repairing matters. When the children repaired their utterances they were more likely to use those forms in later spontaneous speech. In the field of psycholinguistics Michael Tomasello, in particular, has argued for a usage-based theory of language acquisition. His contention is that children learn language by USING language, not only by being immersed in a language-rich environment. To quote the curator of this blog, Dr. Carole Zangari, “language doesn’t grow out of silence” (Zangari, 2016). It behooves us to encourage children and youth with CCN to use their AAC systems as well as having us model their systems with and for them. As the authors suggest it is perhaps because of the additional demands (linguistic, operational, motoric) put on children and youth who are learning to use SGDs what encouraging them to respond, and repair their responses is crucial.

- More than modeling! This article underscores the need to go beyond modeling when providing therapy and scaffolding for those children and youth who are learning to use AAC to communicate and develop language. While the evidence for modeling seems solid (see for example Allen, et al., 2017) it may be that the field needs to look again at our practices and question whether as some, including at some points, unfortunately, myself, have suggested that “modeling (aided language stimulation) all day, every day is desired in AAC, with no requirement of a response.” (ATIA, 2016 cited by Soto, Zangari & Van Tatenhove, 2020).

This article and others mentioned in their review bring that assumption into question. It also, I hope brings the very question of what “modeling” is into question. Soto et al., I believe, challenge us to look deeper and to think deeper about what we know about communication and language development to develop our practices that include aided language stimulation without doubt, but also scaffold, prompt, and overall support AAC development through use by the child.

- Finally, and again perhaps not necessary to say but I will anyway. The conversational interventions, the recasts, and the prompting for repair in the Soto el al. article ALL started by following the child’s lead – that is talking about (communicating about) what THEY were interested in talking about (communicating about) as the starting point. While this certainly is not the main idea of the article, it is I believe something that it reminds of us of, and that perhaps is worth repeating over and over and over – language develops through authentic social interaction, more often than not when the child takes the lead 😉

References

Allen, A. A., Schlosser, R. W., Brock, K. L., Shane, H. C. (2017). The effectiveness of aided augmented input techniques for persons with developmental disabilities: a systematic review.

Romski, M., Sevcik, R. A., Adamson, L. B., Cheslock, M., Smith, A., Barker, R. M., & Bakeman, R. (2010). Randomized comparison of augmented and nonaugmented language interventions for toddlers with developmental delays and their parents. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53(2), 350–64. Ruston, H. P., & Schwanenflu

Soto, G., Zangari, C., & van Tatenhove, G. (2020, January). Beyond AAC Modeling: Effective (Language Instruction for AAC Learners. Pre-conference session presented at the meeting the Assistive Technology Industry Association, Orlando, FL.

Soto, G., & Clarke, M. T. (2017). Effects of a conversation-based intervention on the linguistic skills of children with motor speech disorders who use augmentative and alternative communication. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60(7), 1980–98.

Tomasello, M. (2003). Constructing a language. A usage-based theory of language acquisition. London, UK: Harvard University Press.

von Tetzchner, S. (2017, February). Making the environment communicatively accessible. Webinar for the Alberta CCN Professional Learning Community and the Edmonton Regional Learning Consortium https://arpdcresources.ca/consortia/complex-communication-needs-ccn/?index=8

Zangari, C. (2016) Language Development in AAC. Webinar for the Alberta CCN Professional Learning Community and the Edmonton Regional Learning Consortium

Filed under: Featured Posts, PrAACtical Thinking

Tagged With: language intervention, recasts

This post was written by Carole Zangari

1 Comment

This is really valuable information. I think I need to make myself a visual to remember what kind of recast to use and also build teaching and practicing recasts with my AAC user and all communication partners.

Thanks!