How We Do It: Navigating Successful Post-Secondary Transitions in a Virtual World

AAC professionals can provide a great deal of support to help students prepare for post-school life. Today, guest authors Meredith Gohsman, Jamie Lawson, Heather Patton, and Melanie Melton team up to share their thoughts on helping students who use AAC move successfully toward this transition.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Speech-language pathologists, educators, and other AAC stakeholders all share responsibility in preparing students for successful post-secondary transition. The need to explicitly address post-secondary transition is well-established. Despite benefits of employment for both the employer and employee (McNaughton et al., 2002; McNaughton et al., 2003), individuals using AAC are unemployed at a staggering rate. For individuals using AAC, communication remains a vital component in the workplace (Bryen et al., 2007). Communication interactions and skills are associated with income, as well as job options (Mank et al., 1997; McNaughton & Bryen, 2007; McNaughton & Richardson, 2013). This includes all 5 communicative competencies:

- Linguistic Competence: Mastery of languages in environment and AAC system

- Operational Competence: Mastery of AAC system use

- Social Competence: Mastery of sociolinguistic and sociorelational rules

- Strategic Competence: Mastery of compensatory strategies

- Psychosocial Factors: Motivation, attitude, communication confidence, resilience (Light, 1989, 2003; Light & McNaughton, 2014)

The preparation for post-secondary transition begins at the earliest educational level by incorporating purposeful learning opportunities. These opportunities require careful planning and consideration to be relevant to the students’ preferences, priorities, and goals. To evaluate the transition needs of individuals using AAC, we consulted the resources generated by the National Technical Assistance Center on Transition. This group has reviewed and organized relevant research to support students with disabilities throughout the transition process. By reviewing the evidence, NTACT has identified student skill, career development, collaborative system, and policy predictors of post-secondary success. These predictors are outlined by the level of evidence for success in the domains of education, employment, and independent living.

Using this tool, we identified the predictor skills that can be directly integrated into our work with students using AAC in elementary, middle, and high school. The targeted skills we will be discussing include self-determination and autonomy/decision-making. Both of these predictors are research-based for the post-secondary outcomes of education and employment, as well as promising for the outcome of independent living.

With the knowledge of predictors of post-secondary success, communicative competencies, and the Communication Bill of Rights, we developed a list of skills to explicitly incorporate in our interventions with students using AAC in elementary, middle, and high school. Through our experiences, we also developed a list of corresponding strategies to facilitate the development of the targeted post-secondary success predictors in the context of virtual service delivery.

Linguistic Competence Target Skills

- Build a personal vocabulary for application across language functions and settings.

- Make frequent and meaningful decisions with different communication partners and in different settings.

How We Did It

- Engage students in interactive games and activities and embed opportunities for peer engagement.

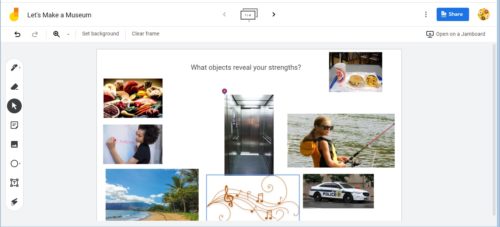

This picture is an example of an activity in which a student selected pictures to represent his/her strengths. This activity can easily be modified to include multiple students, allowing for peer engagement and further discussion of strengths and weaknesses with others. This idea was shared by AAC SLP Sarah Gregory.

This picture is an example of an activity in which a student selected pictures to represent his/her strengths. This activity can easily be modified to include multiple students, allowing for peer engagement and further discussion of strengths and weaknesses with others. This idea was shared by AAC SLP Sarah Gregory.

Operational Competence Target Skills

- Take responsibility for the operation of communication modalities. This may include carrying aided AAC, charging high-technology AAC, manipulating the volume, powering on/off, and cleaning.

- Determine and use the most effective communication modality across settings. Students’ most effective communication modality may differ with the communication partner or setting, such as while on the playground, in the rain, or on the school bus.

How We Did It

- Use tools like Lonely Screen and ScreenCastify to model device care and maintenance.

- Use NearPod and Jamboard to rehearse typing and any word prediction features on students’ AAC modalities.

- Discuss management of aided AAC in the community.

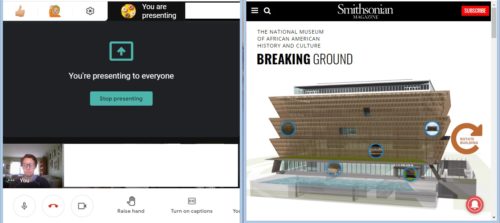

During this virtual field trip to a museum, we discussed how to keep a high-technology AAC system safe in a community place.

During this virtual field trip to a museum, we discussed how to keep a high-technology AAC system safe in a community place.

Social Competence Target Skills

- Use language to argue, negotiate, and express emotions.

- Share frequent opinions and choices. Communication partners must accept and respect these opinions and choices.

How We Did It

- Provide opportunities to join virtual groups with less-familiar communication partners, leading to the development of students’ social networks. These groups may be structured by an area of interest, such as gaming.

- Engage in Virtual Lunch Group with surprise guests.

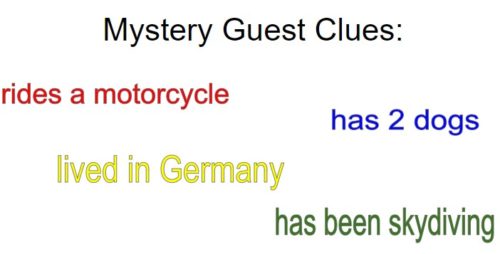

Prepare students for surprise guests by reviewing the guests’ clues, refining questions for a specific communication partner, and discussing possible conversational topics. Guests in the school setting may include friends, teachers, and administrators.

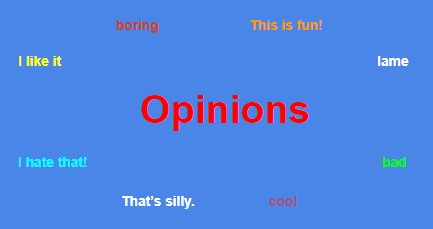

Prepare students for surprise guests by reviewing the guests’ clues, refining questions for a specific communication partner, and discussing possible conversational topics. Guests in the school setting may include friends, teachers, and administrators. - Elicit opinions on activities and personal experiences, including opinions of annoyance, boredom, and dislike.

This includes the exposure and opportunity to use age-appropriate vocabulary to express these opinions.

This includes the exposure and opportunity to use age-appropriate vocabulary to express these opinions.

Strategic Competence Target Skills

- Learn to repair communicative breakdowns. Students can repair breakdowns by determining if a specific communication modality is not working or clarifying when misunderstood. To accomplish this, students must acknowledge all communication modes available for use across settings and communication partners.

How We Did It

- Teach the use of gestures or pre-programmed messages to cue communication partners that a response is forthcoming. These could be phrases such as, “I have something to say.” or “Just a minute please.”

- Incorporate unstructured moments and interactions to allow for misunderstandings, followed by opportunities to repair the communicative exchange. For example, use of strictly structured activities facilitated by adults does not provide the opportunity for students to develop strategic competence.

Psychosocial Competence Target Skills

- Communication partners must always presume competence. This will allow for students to develop confidence and independence as they prepare for post-secondary transitions.

- Access role models. This can be through in-person interactions with other people using AAC or through social media. Students can also see other individuals using AAC on YouTube or TV shows.

How We Did It

- Embed at least one brief tip for communication partners into every virtual session and asynchronous activity.

- Provide parents and caregivers opportunities to network with each other to build their own support. Our facility offers this through monthly virtual parent meetings.

- Include AAC advocacy information in intervention and AAC training. Look for quotes from people who use AAC to help communication partners better understand their role in helping students improve their psychosocial competence.

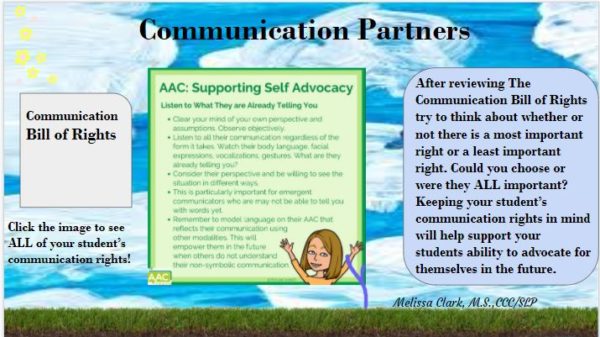

Our colleague used the Communication Bill of Rights and information from The AAC Coach to discuss advocacy with educators.

Our colleague used the Communication Bill of Rights and information from The AAC Coach to discuss advocacy with educators.

Select References

Bryen, D.N., Potts, B.B., & Carey, A.C. (2007). So you want to work? What employers say about job skills, recruitment and hiring employees who rely on AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 23(2), 126-139.

Light, J. (1989) Toward a definition of communicative competence for individuals using augmentative and alternative communication systems. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 5(2), 137-144.

Light, J. (2003). Shattering the silence: Development of communicative competence by individuals who use AAC. In J.C. Light, D.R. Beukelman, & J. Reichle (Eds.), Communicative competence for individuals who use AAC: From research to effective practice (pp. 3 – 38). Paul H. Brookes.

Light, J., & McNaughton, D. (2014). Communicative competence for individuals who require augmentative and alternative communication: A new definition for a new era of communication? Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 30(1), 1–18.

Mank, D., Cioffi, A., & Yovanoff, P. (1997). Analysis of the typicalness of supported employment jobs, natural supports, and wage and integration outcomes. Mental Retardation, 35, 185–197.

McNaughton, D., Light, J., & Arnold, K.B. (2002). “Getting your wheel in the door”: Successful full-time employment experiences of individuals with cerebral palsy who use augmentative and alternative communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 18(2), 59-76.

McNaughton, D., Light, J., & Gulla, S. (2003). Opening up a “whole new world”: Employer and co-worker perspectives on working with individuals who use augmentative and alternative communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 19(4), 235-253.

McNaughton, D., & Bryen, D.N. (2007). AAC technologies to enhance participation and access to meaningful societal roles for adolescents and adults with developmental disabilities who require AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 23(3), 219-229.

McNaughton, D., & Richardson, L. (2013). Supporting positive employment outcomes for individuals with autism who use AAC. Perspectives on Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 22(3), 164-172.

Referenced Links:

- https://transitionta.org/

- https://transitionta.org/sites/default/files/Pred_Outcomes_0.pdf

- https://www.asha.org/njc/communication-bill-of-rights/

- https://www.lonelyscreen.com/

- https://www.screencastify.com/

- nearpod.com

- https://jamboard.google.com/

- https://www.theaaccoach.com/

About the Guest Authors

Meredith Gohsman is a speech-language pathologist and doctoral candidate at Old Dominion University. Her clinical and research interests include AAC interventions for pediatric populations, communication partner training, and collaboration with AAC stakeholders across settings. Meredith is on Twitter @MeredithGohsman. Meredith Gohsman has the following Financial and Non-financial Relationships to disclose: Graduate assistant at Old Dominion University; Employed by Riverside Rehabilitation Hospital; Member of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA); Member of ASHA Special Interest Group 2, 10, and 12

Jaime Lawson currently works in a school setting, servicing students with complex communication needs at New Horizons Regional Education Centers, along with Melonie Melton and Heather Patton. She has previously worked in the outpatient setting, predominantly working with the pediatric population. Her research and therapeutic interests include working with stakeholders to build communicative competence for children with complex communication needs, making it a collaborative effort. Twitter: @JLawSLP Instagram: @j.lawrunner. Jaime has the following Financial and Non-financial Relationships to disclose: Employed by New Horizons Regional Education Centers; Member of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA); Member of ASHA Special Interest Group 12

Heather Patton currently works for New Horizons Regional Education Centers, a regional day program, serving public school students with complex communication needs. Heather has worked in public school and pediatric outpatient settings. Professional interests include collaboration with stakeholders and incorporating literacy with communication. Heather is available on Instagram @hlpslp and Twitter @HLPSLP. Heather has the following Financial and Non-financial Relationships to disclose: Employed by New Horizons Regional Education Centers; Member of the American Speech-Language and Hearing Association (ASHA); Member of ASHA Special Interest Group 12.

Melonie Melton also works at New Horizons Regional Education Centers, currently serving elementary-aged students with autism although her experience ranges from preschool to young adult students with complex communication needs. She has taught coursework in AAC at the university level and provides training in this area with her colleagues, Heather, Jaime, and Meredith locally and beyond. Melonie is available on Twitter @MelonieMelton. Melonie has the following Financial and Non-financial Relationship to disclose: Employed by New Horizons Regional Education Centers, Member of the American Speech-Language and Hearing Association (ASHA), Member of the Speech-Language-Hearing Association of Virginia (SHAV), Member of ASHA Special Interest Group 12.

Filed under: Featured Posts, PrAACtical Thinking

This post was written by Carole Zangari