Beyond the Basics: Thoughts On Effective Language Instruction for AAC Learners

Have you worked with students like these?

- Gaby has been using SGDs since kindergarten. As she approaches high school, Gaby is able to express many things but her language is significantly below those of her peers. This makes it difficult for Gaby to read grade-level textbooks with comprehension, complete writing assignments, and perform well on academic tests.

- Ian’s SLP and teacher are trying to understand why he is able to learn new language skills but seems to lose some of them when they start working on new goal areas. When the time came for a speech-language re-evaluation, they were surprised that Ian scored so poorly in areas where he made mastered his IEP goals.

- Brandon is a fifth grader who wants to go to college someday. His language skills have been growing steadily since he got his first AAC device several years ago, but are still remarkably delayed.

In situations like these, we celebrate the successes in language development that these students have had but also have significant concerns. If the language learning trajectory continues along the same slope, these students will not achieve their language potential and/or realize their personal goals. These sorts of concerns plague AAC professional. How can we expedite the acquisition of targeted language skills and ensure that students retain those skills as they move on to learn new things?

Part of the answer may lie in helping them solidify the new skills that they are learning, and get enough practice with those skills so that they are truly learned and internalized.

That often means that the target skills are on our radar for a long time. That doesn’t mean that we have the same IEP goals year after year, but it does mean that we incorporate this into our instructional planning. For some language skills, we may need to think carefully about our instructional sequences so that the students get adequate preparation for this new skill, sufficient teaching around it, informal assessment to determine how well they are learning it, re-teaching as necessary, and extensive opportunities to practice the new skill.

Gaby, for example, was working on several semantic, pragmatic, and syntactic skills. Tier 2 vocabulary. Unambiguous utterances. Verb phrases. Personal narratives. These are skill areas that take a long time to develop, not because Gaby is a slow learner but because the skills are complex and she has many different things to focus on.

Planned redundancy is one way we can help learners like Gaby. Here are some of the ways we can use that to help her acquire these skills, be able to demonstrate what she’s learned, and maintain her proficiency with those skills over time.

- Consider introducing the skill prior to formally targeting it. Name it, explain it, talk about it, demonstrate it.

- Use focused language stimulation to give copious examples of that skill in various contexts.

- Plan out the instruction so that the scope and sequence is a good match for both the skill and the learner.

- Consider structuring the learning pathway so that it includes periods of awareness-building, direct instruction, practice, and generalization. Using this sort of framework can make a significant difference in their acquisition and internalization of new language skills.

- Re-examine the instructional materials. If you have specific materials, manipulatives, diagrams, worksheets, and/or games, look at them with a critical eye to determine how best to use them. Often this differs from the instructions that come with the materials we’ve purchased, whether from a mainstream publisher or whether they were created by other professionals. Instead of following their directions, use your clinical reasoning to determine how these materials will best serve your student.

- Identify research-supported strategies and determine how to utilize those in your therapy or instructional lesson.

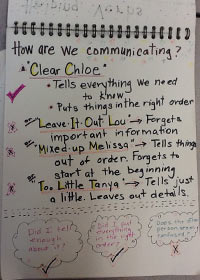

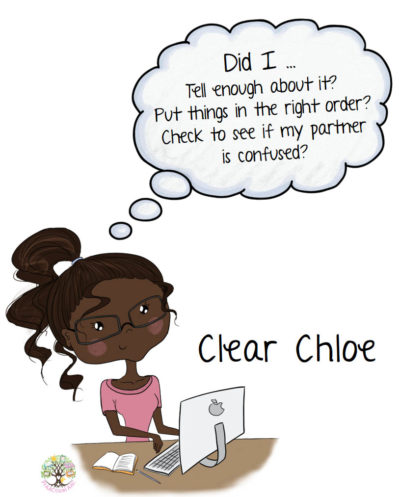

- Use visual supports, particularly those that teach about the skill rather than just reminding the student to utilize the skill. Consider co-creating those with the AAC learner as you move through a sequence of sessions/lessons. Continue to develop the visual supports and add to them as you cover new aspects of the skill.

- Make sure the student knows what his/her specific language goals are and how those skills can help the student achieve his/her own life goals.

- Gather probe data and use it to make course corrections in the intervention plan.

- Collaborate with other team members, particularly parents, so that others can be allies in helping the student understand and use these skills across environments.

Do you have ways of helping AAC learners move beyond the basics in acquiring new language skills? We’d love to hear about them.

Filed under: Featured Posts, PrAACtical Thinking

Tagged With: language therapy

This post was written by Carole Zangari